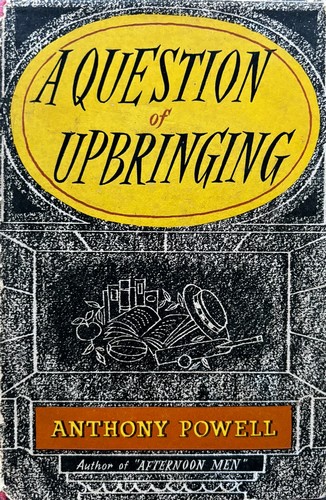

First published 1951 (London: Heinemann; New York: Scribner’s)

A Question of Upbringing opens with a scene of workmen gathered around a brazier on a grey snowy day, an image that reminds the narrator (Nicholas Jenkins) of Poussin’s painting, A Dance to the Music of Time, and which, in turn, takes his thoughts back to a Sunday afternoon at his boarding school. The school resembles Eton, where Powell went to school between 1919 and 1923.

The book’s four chapters center around places:

- Chapter 1: The boarding school and the nearby town.

- Chapter 2: Charles Stringham’s family’s house in London and Peter Templer’s family’s country house, where Nicholas first means Jean, Peter’s sister.

- Chapter 3: La Genardière in central France, where Nicholas goes to improve his French and meets Widmerpool, also staying there.

- Chapter 4: Oxford, where we are introduced to Sillery, his tutor, and Quiggan, a bright and confrontational young man from the North, and London, where Nicholas meets his Uncle Giles once again.

In her guide, Invitation to the Dance, Hilary Spurling provides this timeline for the book:

- Chapter 1: December 1921 to Summer 1922

- Chapter 2: December 1922 to Summer 1923

- Chapter 3: Summer 1923

- Chapter 4: Summer 1924 to Michaelmas term (September to Christmas) 1924

A Question of Upbringing also introduces us to Powell’s choreographic design, in which characters come and go, not so much at random as by accident and coincidence. Nicholas’s Uncle Giles arrives at his school unexpectedly that first Sunday afternoon, then wonders off to Reading (From? He doesn’t say, Nicholas doesn’t know), only to appear again in the book’s last scene: in both cases to press some matter about the trust managed by Nicholas’s father. As others have observed, the movements of characters in and out of Nicholas’s life (and in and out of our view) resembles that of acquaintances in real life. With one exception, though: despite Powell’s cast of hundreds of characters across the twelve volumes of the Dance, it represents a fairly narrow segment of society, even within the limits of English society of the time. This just an observation: the same can be said for any of Jane Austen’s novels. But it can be a stumbling block for the many readers who are unfamiliar with this world (remnants of which remain—e.g., in a good share of Boris Johnson’s cabinet).

Finally, A Question of Upbringing introduces us to Powell’s prose, which can seem archaic to current readers. Even in its most straightforward elements—dialogue—it is suffused with the tendency of the upper-class English to speak elliptically (Uncle Giles tells Nicholas that his issue with the Trust is “Just a question of the trustees,” leaving neither him nor us any more enlightened). This ellipticism works both to protect reputations and dignities and to smear them without seeming to. The trick is to recognize that it’s an idiom that seems ambiguous to us but is often crystal-clear to its users. And when it’s not crystal-clear, it’s usually comical.

But more ornate is Jenkins/Powell’s style in the reflective passages, such as this where he compares his former schoolmates Charles Stringham and Peter Templer:

For example, in the course of having tea for nine months of the year with Stringham and Templer, the divergent nature of their respective points of view became increasingly clear to me, though compared with some remote figure like Widmerpool (who, at that time, seemed scarcely to belong to the same species as the other two) they must have appeared, say to Parkinson, as identical in mould: simply on account of their common indifference to a side of life—notably football—in which Parkinson himself showed every sign of finding absorbing interest. As I came gradually to know them better, I saw that, in reality, Stringham and Templer provided, in their respective methods of approaching life, patterns of two very distinguishable forms of existence, each of which deserved consideration in the light of its own special peculiarities: both, at the same time, demanding adjustment of a scale of values that was slowly taking coherent shape so far as my own canons of behaviour were concerned. This contrast was in the main a matter of temperament. In due course I had opportunities to recognise how much their unlikeness to each other might also be attributed to dissimilar background.

The first two sentences above average 82 words, with multiple dependent clauses; the last two, 16 with none. There’s a clue there: were Powell writing a century or two before, the long sentences would dominate; if he were a lean, mean 20th century prose stylist, the short ones would. In his prose, then, Powell manages to combine both classical and modernist influences, using them to deliberate effect—which is part of what makes this series a special pleasure to read…once you’ve agreed to proceed at Powell’s pace.